SANTIAGO CÓRDOBA WOLF

FOTO: CCENERGY

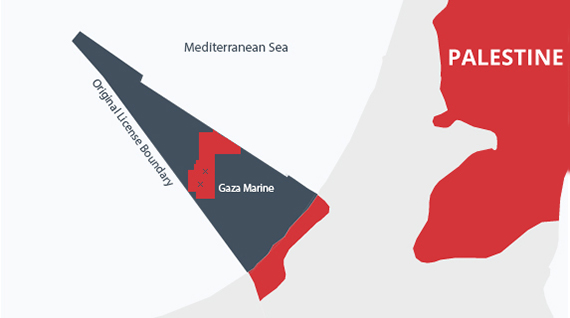

The Gaza Strip, located along the eastern Mediterranean coast, has been at the heart of both geopolitical tensions and economic challenges. Despite Israel’s official withdrawal from the region in 2005, it has maintained substantial control over Gaza’s airspace, territorial waters, and coastal trade routes, as outlined in the Oslo Accords. While these agreements were framed as steps toward Palestinian self-determination, they have, in practice, imposed significant restrictions on the development of Gaza’s natural resources. Chief among these is the Gaza Marine natural gas field, discovered in 1999, approximately 36 kilometers off the coast of Gaza. This local conflict reflects a broader trend of contested energy resources in the Eastern Mediterranean, where states vie for control over increasingly valuable natural reserves.

This resource, with an estimated reserve of 1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, has the potential to meet the energy needs of Palestinian territories while also generating revenue through export. At the time of its discovery, Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat optimistically described Gaza Marine as “a gift from God” that could transform the economic future of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. Annual revenues were projected to exceed $1 billion, which could have spurred economic growth and reduced dependency on external aid. Additionally, the Eastern Mediterranean basin, home to a wealth of undersea hydrocarbon reserves, has become a critical focal point in global energy politics, with competing claims over resources further complicating the region’s dynamics.

However, the political and economic potential of Gaza Marine has been systematically stifled. Agreements like the Oslo Accords (1993) and the Paris Protocol (1994), while nominally granting Palestinians certain rights to resource development, placed ultimate control in Israeli hands. These agreements required Israeli authorization for any resource exploitation and established a shared customs regime managed by Israel, which oversaw critical infrastructure and trade activities. Effectively, this arrangement granted Israel the power to block Palestinian efforts to develop their own resources, ensuring continued economic dependency.

Despite international acknowledgment that Gaza’s natural gas belongs to the Palestinian people under international law, development of the field has been obstructed by Israeli policies. Access to the resource has been further limited by restrictive maritime zones imposed by Israel, which contradict the 20-nautical-mile economic zone outlined in the Oslo Accords. These restrictions, combined with political fragmentation and ongoing blockades, have kept the gas field untapped, leaving its potential economic benefits unrealized.

The Eastern Mediterranean region’s vast hydrocarbon resources, including Gaza Marine and major Israeli gas fields like Leviathan and Tamar, have elevated its importance in global energy markets. Israel has successfully developed its own gas fields, transforming itself into a key energy player while excluding Palestinians from similar opportunities. The geopolitical tensions surrounding the region have only compounded the challenges for Gaza, with its natural resources serving as yet another arena for power struggles rather than economic empowerment.

Historical and Political Context of Gaza Marine

The initial discovery of Gaza Marine in 1999 represented the first serious attempt by Palestinians to exploit their natural resources. Under Arafat’s leadership, the PA signed agreements with British Gas Group (BG) and Consolidated Contractors Company (CCC) for exploration and development. The contracts stipulated that BG would retain 60% of the profits, CCC 30%, and the Palestine Investment Fund (PIF) only 10%. These agreements collectively marginalized Palestinian interests, exacerbated by opaque negotiations and external political pressures.¹

Key PA officials, including Energy Minister Abdul Rahman Ahmed, were excluded from negotiations. Instead, Mohammed Rashid, Arafat’s economic advisor, emerged as the sole representative authorized to act on behalf of the PA. Rashid’s monopolization of negotiations drew intense criticism, particularly following allegations of financial mismanagement after Arafat’s death in 2004. In 2012, Rashid was sentenced in absentia to 15 years in prison for corruption and embezzlement, a conviction he claimed was politically motivated.²

The lack of transparency in these negotiations provided Israel with a pretext to delegitimize Palestinian governance. Israel argued that Palestinian corruption rendered it necessary to “supervise” any resource exploitation, a justification rooted in earlier agreements such as the 1994 Paris Protocol. This agreement granted Palestinians nominal rights to exploit their resources but maintained Israel’s control over infrastructure, permits, and export mechanisms. Israel effectively retained a veto over Palestinian economic autonomy, a system that reinforced dependency and stifled development.³

Further complicating matters, Palestinian access to Gaza Marine has been severely limited by Israeli-imposed restrictions. Although the field lies between 17 and 21 miles off the Gaza coast, the current six-mile fishing and resource limitation, enforced by Israeli forces, directly contravenes the 20-mile area established by the 1993 Oslo Agreements. This restriction prevents Palestinians from fully accessing and developing their own resources, further exacerbating their economic and energy dependency on Israel. Moreover, any potential export of gas would still require Israeli clearance, as Israel controls the critical pipelines necessary for transportation, according to Palestinian officials.⁴

Another significant obstacle lies in the precarious nature of conducting business in a conflict-prone zone. Several sources told Middle East Eye (independent online news outlet) that Gaza Marine represents a minor concession in BG Group’s extensive portfolio, which diminishes the company’s incentive to advocate for its development, especially without guarantees that another war in Gaza isn’t imminent. This lack of security, combined with persistent political fragmentation and blockades, undermines any progress toward leveraging Gaza Marine’s potential to alleviate poverty and energy dependency in the region.⁵

These challenges not only underscore the broader systemic issues but also highlight how external actors and Israeli policies have consistently obstructed Palestinian access to natural resources. As Gaza Marine’s development remains at a standstill, its potential benefits, including job creation, energy independence, and economic revitalization, continue to be unrealized, perpetuating cycles of dependency and deprivation in one of the world’s most impoverished regions.⁶

Missed Opportunities and Consequences for Gaza

In 2003, Joseph Paritzky, Israel’s Minister of Infrastructure, reached an agreement with Fatah during the Second Intifada. The deal proposed that Israel would sell energy resources, some originating from Gaza Marine, back to Palestinians in exchange for reducing the Palestinian Authority’s energy debt to Israel. However, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon ultimately rejected the agreement, arguing that revenues from natural gas could benefit Hamas and fund militant activities. Sharon’s decision not only halted the agreement but also intensified existing tensions, contributing to the escalation of the Second Intifada.⁶

Meanwhile, in 2005, Israel pursued an alternative strategy by finalizing a gas agreement with Egypt, ensuring a reliable energy partnership that excluded Palestinians entirely. This deal further marginalized Palestinian claims to Gaza Marine and solidified Israel’s control over regional energy markets.⁷

By 2006, further secret agreements emerged between the Israeli government and Mahmoud Abbas’s faction within the Palestinian Authority. Following the January 2006 elections that resulted in a Hamas-dominated PA government, both parties agreed that revenues from Gaza Marine would be transferred through an international account inaccessible to the official PA leadership. The terms of the BG Group-Israeli purchase were also revealed: Israel would purchase 0.05 trillion cubic feet of Palestinian gas for $4 billion annually, with the gas piped to Ashkelon for liquefaction in Israel. This arrangement would primarily supply the Israeli market, covering only limited energy needs in Gaza while bypassing Palestinian control entirely.⁸

These resource restrictions have had severe socioeconomic implications for Gaza’s population. Unemployment rates in Gaza have consistently remained among the highest in the world, reaching 45% in 2022, with youth unemployment exceeding 60%.⁹

The inability to develop Gaza Marine further compounds these challenges, as an estimated 10,000 jobs could have been created through gas field development and its associated industries. The blockade and restricted economic access have also halved Gaza’s GDP per capita since the early 2000s, leaving over 80% of the population dependent on international aid for survival. These grim statistics highlight how the obstruction of Gaza Marine has contributed to a cycle of economic stagnation and despair.¹⁰

Journalist Dania Akkad highlights how Israel’s control over Gaza’s energy resources is part of a broader strategy to use economic domination as a tool of political control. The development of Gaza Marine could have alleviated poverty and reduced Palestinian dependency on imported energy while addressing chronic electricity shortages, which leave Gaza residents with as little as four hours of electricity daily. However, Israeli blockades and political fragmentation within Palestinian leadership have consistently undermined these opportunities.¹¹

Paritzky’s failed deal with Fatah and the subsequent agreement with Egypt underscore how Israel has leveraged energy resources to maintain economic and political dominance while denying Palestinians sovereignty overtheir natural wealth.¹²

Israeli Intervention, The Rise of Hamas, and The Control of Gaza Marine

Israel’s consistent opposition to Palestinian sovereignty over Gaza Marine reflects its broader strategy to monopolize regional resources under the guise of security concerns. When Hamas won the 2006 parliamentary elections, the situation worsened significantly. Israel imposed a blockade on Gaza, claiming that gas revenues could potentially fund Hamas’s military activities. While this justification was publicly framed as a security concern, many experts argue that it masked broader Israeli strategies to monopolize regional energy markets and maintain control over Palestinian resources.¹³

The rise of Hamas complicated international negotiations over Gaza Marine. By asserting control over Gaza, Hamas’s leadership introduced new dynamics that made it more difficult for external actors, including Israel and multinational corporations, to justify engaging in resource-sharing agreements. International skepticism toward Hamas, coupled with existing Israeli narratives framing the group as a terrorist threat, created an impasse. Attempts to sideline Hamas, such as directly negotiating with the Palestinian Authority (PA) or third-party nations like Egypt, only deepened the fragmentation of Palestinian leadership and hindered progress.¹⁴

Adding to the complexity, Israel’s military intervention in 2008, known as “Operation Cast Lead,” was officially presented as an effort to dismantle Hamas’s “terrorist” activities. Analysts, however, interpreted it as a move to solidify Israeli control over Gaza Marine.¹⁵

This period also coincided with heightened energy ambitions in Israel. Shortly after Operation Cast Lead, Israel announced the discovery of the Leviathan gas field, the largest natural gas deposit ever found in the Levant Basin. Combined with the earlier discovery of Tamar, these finds allowed Israel to transition from an energy importer to a regional energy powerhouse by 2018, significantly reducing its dependency on external energy sources.¹⁶

Despite this, new rounds of negotiations over Palestinian gas fields emerged by 2014. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, with Quartet Representative Tony Blair, advocated for Palestinian gas field development in rhetoric that emphasized cooperation. Yet these discussions stalled, with Hamas rejecting any agreement that excluded its participation and emphasizing the illegitimacy of deals conducted without the input of Gaza’s government. This ongoing resistance reinforced the fragmentation of governance over Gaza’s resources, further impeding the realization of Gaza Marine’s potential.¹⁷

Meanwhile, Israel continued to consolidate its regional energy dominance through agreements like the $1.2 billion supply deal between the Palestine Power Generation Company (PPGC) and Israel’s Leviathan field. Such deals, while ostensibly aimed at supporting Palestinian infrastructure, entrenched dependency on Israeli-controlled resources and excluded Gaza’s population from the benefits of its natural wealth. These developments illustrate a broader strategy of economic domination, using narratives of security and governance inefficiency to marginalize Palestinian claims and prevent their full participation in the regional energy economy.¹⁸

Geopolitical Expansion and the Levant Basin

Israel’s expansionist energy policies must be understood within the broader context of the Levant Basin, an energy-rich region valued at approximately $453 billion. While Palestinians have been denied access to Gaza Marine, Israel has successfully developed major offshore gas fields, including Tamar (discovered in 2009) and Leviathan (2010), which began production in 2013 and 2019, respectively. These discoveries marked a turning point for Israel, as the country transitioned from being energy-dependent to an energy powerhouse. Leviathan alone, covering 325 square kilometers, contains 22 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.¹⁹

This rapid success fulfilled Israel’s ambition to position itself as a key energy supplier to Europe, especially in the aftermath of Europe’s efforts to diversify away from Russian energy supplies. Projects like the EastMed pipeline, designed to transport gas from Israeli and Cypriot waters to Europe via Greece, exemplify this strategy. Recognized as a “Project of Common Interest” by the European Union, EastMed has strengthened Israel’s economic ties to Europe while systematically isolating Palestinians from participating in the regional energy economy.²⁰

Israel’s efforts to consolidate control over the region’s gas resources have not been without geopolitical complications. In 2022, Israel and Lebanon, two long-standing adversaries, reached a maritime border agreement mediated by the French energy company Total Energies. This agreement aimed to resolve disputes over the Qana gas field, situated near the Golan Heights (territory seized by Israel in 1967) and the Lebanese border. Although the division favored Israel, it also brought temporary economic relief to Lebanon, a country grappling with a decade-long financial crisis.²¹

At the same time, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) positioned itself as a guarantor of the agreement. To ensure the project’s implementation, the UAE negotiated directly with the Hezbollah militia, which dominates southern Lebanon, securing their commitment to refrain from attacking the gas infrastructure. This delicate compromise allowed all involved parties to assume their respective shares in the project, marking a rare moment of pragmatic cooperation in the region.²²

Encouraged by the success of the Lebanon agreement, Israel sought to replicate this formula in July 2023 with the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Egypt to revive the Gaza Marine project. However, Israel deliberately bypassed Hamas, which controls Gaza, ignoring the PA’s lack of authority in the region. Instead, Israel exclusively negotiated with Egypt to construct a pipeline from Gaza Marine to Egyptian territory. Hamas, reportedly receiving Israeli assurances not to interfere with the project, agreed to the terms.²³

Under this arrangement, a portion of the gas would be exported to Egypt, generating some revenue for the people of Gaza. However, most of the gas would serve to supply energy for the Gaza Strip, addressing chronic energy shortages and further entrenching economic dependency on external actors.²⁴

Israel’s ability to leverage regional agreements and secure its own energy dominance reflects the systemic marginalization of Palestinians. The discovery of Leviathan and Tamar provided Israel with an alternative to Gaza Marine, which further solidified its control over regional resources while circumventing Palestinian participation. By 2018, Israel had achieved 60% energy self-sufficiency, positioning itself as a regional energy leader and expanding its geopolitical influence in the Eastern Mediterranean.²⁵

This series of developments highlights Israel’s strategic approach to energy politics: using bilateral agreements, regional diplomacy, and infrastructural projects to secure its role as a dominant energy supplier while ensuring that Palestinians remain excluded from their natural wealth. The Gaza Marine gas fields, though rich with potential, continue to symbolize the broader struggle over sovereignty, economic justice, and geopolitical power in the region.²⁶

The agreements forged by Arab nations illustrate how energy diplomacy has pushed and continues to push regional actors to bridge divides with their long-standing adversaries. These three pivotal developments—the accord between Lebanon and Israel, the deal between Tel Aviv, Cairo, and the Palestinian Authority, and the agreement involving the European Union, Israel, and Egypt—have established the foundation for a new regional energy alliance.²⁷

Genocide in Gaza and the Geopolitical Implications of Natural Gas Reserves

The Gaza Strip, long a focal point of geopolitical tension, remains at the confluence of humanitarian crises and natural resource politics. Allegations of genocide committed by Israel have been substantiated by human rights organizations citing the systematic deprivation of essential services, destruction of civilian infrastructure, and blockade-induced scarcity that exacerbates Gaza’s already dire conditions. Amid this humanitarian crisis, the untapped natural gas reserves off Gaza’s coast introduce another layer of complexity, raising questions about whether resource control underpins the ongoing genocide.²⁸

The Gaza Marine field, containing an estimated 1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, exemplifies the region’s potential wealth in stark contrast to the entrenched poverty of its population. While under international law, Palestinians maintain sovereign rights over these resources, Israeli-imposed blockades and maritime restrictions have effectively barred their exploitation. The systematic prevention of development, coupled with the monopolization of energy resources across the Eastern Mediterranean, suggests a deliberate effort to marginalize Palestinian economic independence.²⁹ Israel’s blockade and its justification under «security concerns» serve not only to weaken Hamas’s operational capacity but also to reinforce Israeli control over regional energy markets.

This deliberate weakening of Palestinian socio-economic structures complements Israel’s broader strategy of consolidating resource control, underscoring the interplay between humanitarian and geopolitical objectives.

The Eastern Mediterranean’s vast hydrocarbon reserves, including Israel’s Leviathan and Tamar fields, have elevated the geopolitical stakes. As Israel has transitioned into an energy exporter, its reliance on domestic reserves diminished, reducing any potential energy dependency on Gaza Marine. This development has, in turn, removed incentives for Israel to negotiate equitable resource-sharing agreements. The sidelining of Palestinian claims is further compounded by strategic initiatives like the EastMed pipeline, which bypasses Gaza and connects Israeli and Cypriot gas fields directly to European markets.³⁰

Evidence from international legal frameworks underscores the illegitimacy of Israel’s policies in denying Palestinian access to these resources. Despite agreements such as the Gaza-Jericho Accord, which established Palestinian rights to a 20-nautical-mile economic zone, Israel has persistently restricted Gaza’s maritime access, ostensibly for security purposes. However, these restrictions reflect broader strategies to ensure economic dependency and maintain leverage over Palestinian leadership.³¹

The suppression of resource development is emblematic of a larger pattern of economic exclusion that intertwines with the genocide. The destruction of infrastructure critical for basic survival—such as water and electricity facilities—has been described as part of a systematic campaign to undermine Gaza’s viability as a functioning society. This strategy, combined with the obstruction of natural gas exploitation, reflects a calculated effort to deny Palestinians the economic means to assert sovereignty or achieve self-sufficiency.

The international community’s role in addressing this dual crisis of genocide and resource control remains insufficient. While the approval of the Gaza Marine project in 2023 offers a nominal step forward, it is accompanied by stipulations requiring Israeli security oversight and partnerships with Egyptian entities. This arrangement effectively bypasses Hamas and entrenches economic dependency on external actors. Moreover, revenues from these resources are unlikely to translate into substantial economic relief for Gaza’s population under the current geopolitical framework.³²

The intersection of humanitarian deprivation and natural resource politics necessitates a holistic approach to resolving the conflict. Any sustainable solution must prioritize not only an end to the blockade and genocidal practices but also the establishment of mechanisms that guarantee Palestinian rights to their natural resources. Such measures would be essential not only for alleviating the humanitarian crisis but also for promoting economic self-determination as a foundation for lasting peace in the region.³³

Israel’s Framing of Hamas and the Geopolitical Narrative Today

In the wake of Hamas’s attacks on October 7, 2024, Israel has framed its actions in Gaza as a defensive measure aimed at eliminating Hamas. This justification has been used to perpetuate a narrative of self-defense, even as the scale of destruction in Gaza reveals far more extensive objectives. International observers have noted the striking passivity of Western powers, whose continued support has facilitated the extermination of Palestinian society and culture. The rhetoric surrounding «self-defense» masks the systematic targeting of civilians, infrastructure, and cultural heritage under the guise that «Hamas was there,» regardless of the actual presence of combatants.³⁴

Moreover, this abstraction of Hamas as an omnipresent threat has allowed Israel to carry out extensive military operations. For instance, the assassination of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in July 2024 served not to weaken Hamas but to obstruct peace efforts, as Haniyeh had been engaged in ceasefire negotiations. Israel’s broader strategy is not aimed at achieving peace but rather at sustaining conflict to further territorial expansion, from the river to the sea. This manipulation of language and narratives remains central to Israel’s approach, as seen in its ongoing campaign in southern Lebanon, where Hezbollah has become the new pretext for aggressive military actions.³⁵

Hamas, Resistance, and the Political Context

Hamas has demonstrated significant resilience despite facing nearly a year of genocidal violence supported by major world powers. While opinions within Gaza about Hamas vary, the movement’s popularity outside the territory has grown as it is increasingly seen as the sole defender of Palestinian rights.³⁶

Tareq Baconi notes in his essay Hamas: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance (2024) that Hamas’s existence and actions must be analyzed within the broader context of over 60 years of occupation and systematic restrictions imposed by Israel and the United States.³⁷

Baconi emphasizes that labeling Hamas or Hezbollah as mere «terrorist organizations» erases the political context of their resistance. This framing allows Israel to present itself as a democratic nation acting in self-defense, a narrative that obscures the nationalistic and anti-occupation nature of Hamas’s struggle. Interestingly, while Israel portrays Hamas as a threat to its existence, it has historically facilitated the group’s presence in Gaza as a means of justifying the blockade. Even if Hamas were to disappear, the blockade and the broader framework of control over Palestinian autonomy would likely remain intact.³⁸

This geopolitical strategy is further linked to economic incentives, such as the one explained in this paper: reserves in Gaza Marine. While no significant reserves have been confirmed in the West Bank, Israeli interest in potential energy resources in occupied territories underscores the strategic dimension of its actions. The continued dependence of Gaza and the West Bank on Israeli-controlled resources, entrenched by agreements like the 1994 Paris Protocol, perpetuates this dynamic. Exploiting Palestinian gas reserves could reduce this dependency, but it poses a strategic risk to Israel’s long-term objectives of maintaining control over the region.³⁹

Resource Appropriation, Strategic Control, or a New Pretext for Radical Zionism?

Unlike the West Bank and other formerly Palestinian territories, Gaza holds no ideological significance for Zionism. There are no sacred sites or ancient myths of Hebrew ethnonationalism tied to Gaza. The region has always been a strategic obstacle rather than a desirable possession in the Israeli project.⁴⁰

As the second year of systematic genocide in Gaza progresses, with Israel expanding its war efforts into Lebanon and now Syria following the decline of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, there is little indication that Tel Aviv intends to cease its operations. Even less likely is any meaningful intervention from Western allies, particularly the United States, which has consistently supported Israeli actions, either explicitly or through passive complicity.⁴¹

Israeli authorities are acutely aware that fully dismantling Hamas is an impossible task. From the outset of the conflict, the widely propagated claim of «rescuing hostages» served more as a political and international justification for unchecked violence than as an actionable objective. With this narrative now exhausted and discredited, Israel persists in its campaigns of destruction under the guise of its «right to defend itself.» This facade only serves to obscure its ultimate objective: the complete eradication of Gaza.⁴²

The long-standing strategy of isolating Palestinians has proven both logistically challenging and unsustainable. The current approach, shrouded in media distortions, is alarmingly straightforward: total ethnic cleansing. Although Israel may no longer require Gaza Marine’s natural gas or other Palestinian resources directly, its colonial and capitalist ethos drives it to continuously seek dominance, encouraged by unwavering American support.⁴³

Gaza in the Context of Regional Aggression and Resource Control

To comprehend the broader motivations behind Israeli actions in Gaza and its surrounding territories, one must also consider developments in Lebanon, Syria, and Iran. Although Israel consistently frames its military operations and territorial occupations as responses to armed threats from groups such as Hamas, Hezbollah, and Iranian-backed militias, the economic and energy dimensions cannot be ignored. The strategic annexation of areas with significant economic potential, including Lebanon’s maritime reserves and the Golan Heights water and energy resources, reveals a calculated agenda.

The Golan Heights: Strategic and Economic Importance

The relationship between Syria’s prolonged civil war, the weakening of Assad’s regime, and Israel’s expedited actions in the Golan Heights highlights a carefully orchestrated strategy. Occupied since the 1967 Six-Day War and unilaterally annexed by Israel in 1981, the Golan Heights is a region of immense geopolitical and economic significance. Its location provides a natural defensive barrier against Syria, while its resources, particularly water and potential oil and gas reserves, add substantial economic value.⁴⁴

During Syria’s internal conflict, Israel accelerated infrastructure and exploration projects in the Golan Heights, solidifying its occupation and securing exclusive access to these resources.⁴⁵

The collapse of centralized governance in Syria allowed Israel to justify its actions as necessary for national security, citing concerns over Iranian influence and Hezbollah’s growing presence. However, these security narratives mask, once again, a broader economic strategy. By capitalizing on Syria’s instability, Israel ensured exclusive control over the Golan’s resources, positioning itself advantageously in the region’s future energy landscape.⁴⁶

Similar to its actions in Gaza, Israel’s strategic exploitation of the Golan Heights underscores a broader pattern of leveraging regional instability to consolidate resource control and geopolitical influence.⁴⁷

Geopolitical Implications and Future Considerations

Israel’s actions in the Golan Heights reflect a broader trend in its regional strategy. By embedding economic and resource-driven motives within its military and territorial policies, Israel has managed to both secure immediate gains and establish long-term advantages in regional geopolitics. The ongoing destruction in Gaza, the annexation of resource-rich territories, and the systematic marginalization of Palestinian economic autonomy must be understood as interconnected elements of a unified strategy.

The systematic targeting of territories like Gaza and the Golan Heights goes beyond security concerns, serving as a means to consolidate control over resources critical to Israel’s economic and geopolitical ambitions. Whether through direct appropriation or the strategic marginalization of neighboring states and populations, Israel’s actions underscore the role of resource control in shaping its broader regional agenda. As the international community continues to grapple with these dynamics, the intersection of energy politics and human rights violations in Gaza and beyond demands urgent attention.

International mediation and enforcement of Palestinian resource rights, alongside efforts to lift the blockade, are essential steps toward addressing the economic and humanitarian crises in Gaza. Key measures include:

- International Legal Action: International organizations such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC) could be tasked with enforcing Palestinian rights over their natural resources, as enshrined in international law, to challenge the legitimacy of Israel’s resource appropriation policies.⁵⁰

- Economic Sanctions and Incentives: Targeted sanctions on companies and states benefiting from the exploitation of Palestinian resources can pressure stakeholders to adopt more equitable resource-sharing frameworks. Conversely, international funding mechanisms could incentivize sustainable development of Gaza’s resources under Palestinian leadership.⁵¹

- Humanitarian Intervention: United Nations agencies and non-governmental organizations must scale up efforts to alleviate the immediate humanitarian crisis in Gaza. This includes rebuilding infrastructure critical for water, electricity, and healthcare systems destroyed during the genocide.⁵²

- Regional Diplomatic Engagement: Arab states and other regional actors, such as Egypt and Jordan, should play a more active role in advocating for the enforcement of Palestinian economic sovereignty. Regional cooperation could also facilitate the equitable distribution of energy resources.⁵³

- Energy Development Frameworks: International stakeholders, including the European Union, could sponsor neutral third-party frameworks to oversee the development of Gaza Marine and other regional energy projects. These frameworks would ensure revenue transparency and equitable allocation of resources to benefit Palestinian communities.⁵⁴

- Accountability Mechanisms: Independent monitoring bodies should be established to ensure compliance with any agreements reached, including lifting the blockade, allowing maritime access, and guaranteeing Palestinian participation in resource-sharing decisions.⁵⁵

These steps collectively aim to tackle the intertwined crises of resource control and humanitarian violations. Without significant international intervention and regional cooperation, the status quo will continue to perpetuate economic dependency, political oppression, and ongoing cycles of violence.

Conclusion

The persistent marginalization of Gaza’s natural resources, epitomized by the Gaza Marine gas field, is a testament to the broader systemic strategies of economic control, geopolitical dominance, and political subjugation that have long defined the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Through restrictive maritime zones, political fragmentation, and militarized interventions, Israel has entrenched a framework of dependency that not only stifles Palestinian economic self-sufficiency but also exacerbates the humanitarian crises plaguing Gaza’s population.

At its core, the suppression of Gaza Marine’s potential highlights the interplay between resource control and the denial of sovereignty. While Israel has positioned itself as a regional energy monster, leveraging discoveries such as Leviathan and Tamar to cement its geopolitical influence, Palestinians remain excluded from participating in the economic benefits of their own natural wealth. This exclusion is not incidental but part of a calculated strategy that intertwines military, economic, and diplomatic maneuvers to consolidate control over the region’s energy resources.

As the humanitarian crisis in Gaza deepens, the link between the genocide and resource appropriation becomes increasingly clear. The systematic destruction of infrastructure, the deprivation of basic services, and the economic exclusion of Palestinians from their own natural resources reflect a deliberate weakening of socio-economic structures, designed to perpetuate dependency and undermine self-determination. The blockade on Gaza, framed under the guise of security concerns, serves as a mechanism to reinforce these dynamics while obscuring the broader objectives of territorial and resource domination.

The stakes of this conflict extend far beyond Gaza, influencing the geopolitical landscape of the Eastern Mediterranean and shaping the global energy economy. The region’s contested hydrocarbon reserves have become a focal point for international competition, with Israel’s alliances and energy projects systematically marginalizing Palestinian claims. In this context, the struggle over Gaza Marine is not merely a localized conflict but a microcosm of broader power dynamics, where the intersection of energy politics and human rights violations demands urgent international attention.

A sustainable resolution to this dual crisis requires a comprehensive approach that prioritizes both humanitarian relief and the enforcement of resource rights. International mediation, regional cooperation, and the establishment of transparent energy frameworks are essential to addressing the root causes of Gaza’s economic deprivation. Without such efforts, the cycle of violence, dependency, and dispossession will persist, undermining the prospects for justice and peace in the region.

In conclusion, Gaza Marine stands as both a symbol and a battleground of potential prosperity obstructed by entrenched inequities and of a conflict where resource control perpetuates oppression. Addressing this injustice is not only a matter of economic fairness but also a prerequisite for breaking the cycles of humanitarian suffering and political subjugation that define Gaza’s reality. Only through coordinated international action and a steadfast commitment to upholding Palestinian sovereignty can the region move toward a future rooted in equity, stability, and peace.

References

· Al Jazeera. «Analyzing the Hostage Narrative and Israeli Objectives in Gaza.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.aljazeera.com/hostage-narrative-and-israel-gaza.

· Al Jazeera. «How Gaza Blockade Is Used to Justify Israeli Military Actions.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/7/20/gaza-blockade-and-justifications.

· Al Jazeera. «Israel and Lebanon Maritime Agreement Mediated by Total Energies.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/11/5/israel-lebanon-maritime-agreement.

· Al Jazeera. «Palestine’s Forgotten Oil and Gas Resources.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2021/6/21/palestines-forgotten-oil-and-gas-resources.

· Associated Press. «Israel, Palestinians, Hamas War: Gaza Reconstruction.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://apnews.com/article/israel-palestinians-hamas-war-gaza-reconstruction-un-0ac47ddba7401e102b2bb95e85f3e105.

· Associated Press. «Israel, Palestinians, Hamas, Gaza Genocide, Human Rights Watch.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://apnews.com/article/israel-palestinians-hamas-gaza-genocide-human-rights-watch-0cae5c250415975ebbfcfdab6808abc4.

· Associated Press. «UN, Israel, Palestinians, Norway: Gaza Court Resolution.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://apnews.com/article/un-israel-palestinians-norway-gaza-court-resolution-5661d41477c97129c45bb37465d9e3de.

· Baconi, Tareq. Hamas: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance. 2024.

· Banco Mundial. «GDP per Capita in Palestine.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=PS.

· Banco Mundial. «West Bank and Gaza Overview.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/westbankandgaza/overview.

· EastMed Pipeline Project. «Ensuring Fair Energy Development in the Eastern Mediterranean.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.eastmed-project.eu/equitable-energy.

· EastMed Pipeline Project. «Regional Infrastructure Collaboration for Energy.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.eastmed-project.eu.

· Globalización. «Guerra y Gas Natural: La Invasión Israelí y los Campos de Gas Marinos de Gaza.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.globalizacion.ca/guerra-y-gas-natural-la-invasion-israeli-y-los-campos-de-gas-marinos-de-gaza/.

· International Court of Justice. Advisory Opinion on Palestinian Resource Rights. Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.icj-cij.org/case-policies.

· La Razón. «El Gas del Líbano También Importa.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.larazon.es/economia/gas-libano-tambien-importa_2024100667020c4a64da620001771407.html.

· Oficina Central Palestina de Estadísticas. «Indicadores Principales.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/post.aspx?ItemID=4421&lang=en.

· Público. «Economic Dependency Through Energy Agreements.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.publico.es/energia-dependency-agreements.

· Público. «Israel Trató de Aislar Gaza pero No Pudo: Ahora, la Única Propuesta es Exterminar a los Palestinos.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.publico.es/internacional/israel-trato-aislar-gaza-pudo-hacerlo-ahora-unica-propuesta-exterminar-palestinos.html.

· Público. «Leveraging Instability: The Golan Heights and Israeli Expansionism.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.publico.es/leveraging-instability-israel-golan.

· Público. «The Geopolitical Impacts of Regional Energy Alliances.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.publico.es/internacional/geopolitics-energy-alliances.

· Público. «The Geopolitical Impacts of Resource-Control Policies.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.publico.es/resource-control-israel-policies.

· Público. «Yacimientos de Gas en la Franja de Gaza: Un Casus Belli.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.publico.es/internacional/yacimientos-gas-franja-gaza-casus-belli-jugoso-botin-colateral.html.

· Statista. «Unemployment Rate in Palestine.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1423918/unemployment-rate-in-palestine/.

· Statista. «Youth Unemployment Rate in Palestine.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1423945/youth-unemployment-rate-in-palestine/.

· TASAM. «Yeni Deniz Güvenliği Ekosistemi ve Doğu Akdeniz.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://tasam.org/Files/Icerik/File/yeni-deniz-guvenligi-ekosistemi-ve-dogu-akdeniz_EKT_y-207-248_pdf_da7eb8ae-141f-479f-8883-83c1199607b2.pdf.

· Tony Blair. Advocating Energy Development in Palestine: A Report for the Quartet. Jerusalem: Quartet Office, 2014.

· UNCTAD. Gaza: Unprecedented Destruction Will Take Tens of Billions of Dollars and Decades to Reverse. Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://unctad.org/news/gaza-unprecedented-destruction-will-take-tens-billions-dollars-and-decades-reverse.

· UNCTAD. Prior to Current Crisis, Decades-Long Blockade Hollowed Gaza’s Economy, Leaving 80%. Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://unctad.org/press-material/prior-current-crisis-decades-long-blockade-hollowed-gazas-economy-leaving-80.

· UNRWA. «UNRWA Situation Report 147: Situation in Gaza Strip and West Bank Including East Jerusalem.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.unrwa.org/resources/reports/unrwa-situation-report-147-situation-gaza-strip-and-west-bank-including-east-jerusalem.

· United Nations Environment Programme. «Damage in Gaza Causing New Risks to Human Health and Long-Term Recovery.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/damage-gaza-causing-new-risks-human-health-and-long-term-recovery.

· World Food Programme. «Gaza: Urgent Action Needed as Hunger Soars to Critical Levels.» Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.wfp.org/stories/gaza-urgent-action-needed-hunger-soars-critical-levels.

· World Health Organization. Rebuilding Gaza: The Role of Healthcare Infrastructure in Post-Conflict Zones. Accedido el [fecha de acceso]. https://www.who.int/gaza-healthcare-recovery.